We love the mob-wife aesthetic but did you know about it's dark past?

The trend, deeply rooted in the underbelly of mafia culture, speaks of generations of women who have donned clothing as armour.

For years, the language of high fashion has spoken in whispers of the mob wife archetype. The bold jewels and dramatic shoulders of Schiaparelli, the sinuous leather and figure-hugging silhouettes of Alaïa, the opulent pronouncements of Italian houses like Versace and Dolce & Gabbana—all have echoed in the corridors of couture. Yet, it was the TikToks of influencer Sarah Jordan Arcuri, the self-proclaimed “Mob Wife Aesthetic CEO,” and Kayla Trivieri that ignited the inferno. Kayla’s viral video featured a tongue-in-cheek decree via photos of The Sopranos’ Carmela Soprano—“Clean girl is out; mob wife era is in, okay?”—and suddenly, the mob wife aesthetic was a global phenomenon.

“I hear the ‘mob wife aesthetic’ is making a comeback…,” mused Francis Ford Coppola, the director of The Godfather himself, on his Instagram. He then revealed how his wife’s wardrobe informed the sartorial choices of Diane Keaton’s Kay Adams-Corleone. Soon, editorial spreads and social media feeds were awash with fur coats, chunky hoops, and voluminous hair, replacing the sleek buns and beige palettes of the recent past. However, like many a fleeting fancy, the mob wife aesthetic seems to have forgotten the shadows that birthed it.

Fashion has long served as a shield, a means of self-presentation that offers a sense of security and power. This trend, deeply rooted in the underbelly of mafia culture, speaks of generations of women who have donned clothing as armour. Existing in a world that values them primarily for their association with powerful men, these women weaponise bold silhouettes and dramatic make-up, a façade to mask the perpetual instability that surrounds them. The mob wife’s exterior projects the sensual confidence and heroic valour that the reality of life within organised crime demands. The allure lies in the illusion of power, a power that ultimately remains unrealised.

The notion of the ‘cherished wife’, who is capable of softening a hardened criminal’s heart, holds a strange fascination for the outside world. Images are painted of these wives showered with lavish gifts, shielded from harm, and living on their own terms. Yet, films, documentaries, and harsh realities tell a different story. It is a life lived under the constant threat of losing everything, with a partner who often views you as an ornament, not an equal. The new set of jewels might arrive only after the discovery of an instance of infidelity, the sunglasses nicely mask the sleepless nights, and the red lipstick is a desperate attempt to blend out the crimson of an open wound.

The mob wife aesthetic, a rebellion against the hushed tones of quiet luxury, and the naivety of girlcore, aspires to project a more mature image. It embodies a strong woman, one who is secure. However, it glamorises the complexities of true adulthood, especially one that is riddled with wrongdoings. While not a direct glorification of criminal life, it trivialises the experiences of the women who truly inhabit this world. One could also argue that the trend appropriates the culture of many immigrant communities, once mocked and marginalised for their over-the-top fashion.

On the other hand, the obsession with the mob wife hints at a resurgence of maximalism, a comeback to the chaos of life. Like the mob wife herself, it betrays a subconscious awareness of all it seeks to hide. While coquettish trends may have offered solace in a world with dwindling hope, the embrace of bolder aesthetics tells of a return to a more nuanced reality. Perhaps, it is a subtle subversion, a challenge to the judgmental gaze that scrutinises a bold woman who has been dealt a difficult hand, a woman whose power lies only in what she chooses to wear.

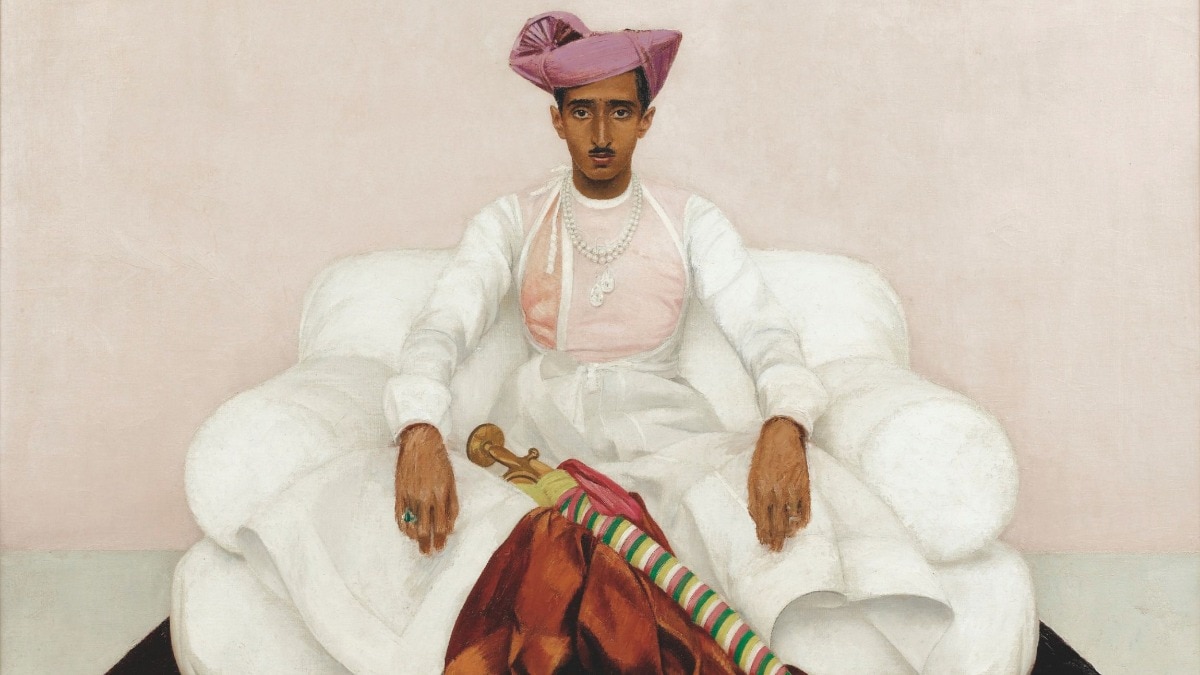

Feature Image: Mary with her husband Simone DeCavalcante in Trenton

All images: Getty Images

This article originally appeared in Harper's Bazaar India, April-May 2024 print issue.

Also Read: Oversized bags steal the spotlight this summer

Also Read: These iconic accessories are all you need for a sophisticated, yet edgy, look