How Yeshwant Rao Holkar II’s sartorial experiments transformed Indian royalty

It was minimalism, avant-garde, modernism, and simplicity.

Hair slicked back, a young maharaja smiles to himself as he attempts to light a cigarette, waiting for Man Ray to finish photographing him. An image of candid poise, the double platinum links of a Cartier Tank watch almost hide away the dial, adorning his left hand daintily, while on his right hand is a ring designed by the French jeweller Raymond Templier—the only two pieces of jewellery on the young Yeshwant Rao Holkar II. “Minimalism, avant-garde, modernism, and simplicity,” notes art historian Géraldine Lenain, the author of The Last Maharaja of Indore, an upcoming book on the life and times of the maharaja. “That was his chic.”

A diamond-lined brooch-bar, set with rubies, sapphires and emeralds, commissioned by the Maharaja in July 1928. Chaumet collections (Paris).

Ray had been introduced to the maharaja by the latter’s new-found friend Henri-Pierre Roché. “The Maharaja of Indore came to the studio to be photographed,” he writes in his autobiography. “Also in Western clothes— sack suits and formal evening dress.” By the roaring twenties, Paris had become a shopping destination for the affluent, which included Indian royalty who were spending extended amounts of time abroad—Gayatri Devi recalled her mother placing orders for mousseline de soie nightgowns in Paris before her wedding, while Maharaja Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala would enter the House of Worth every time he was in the city.

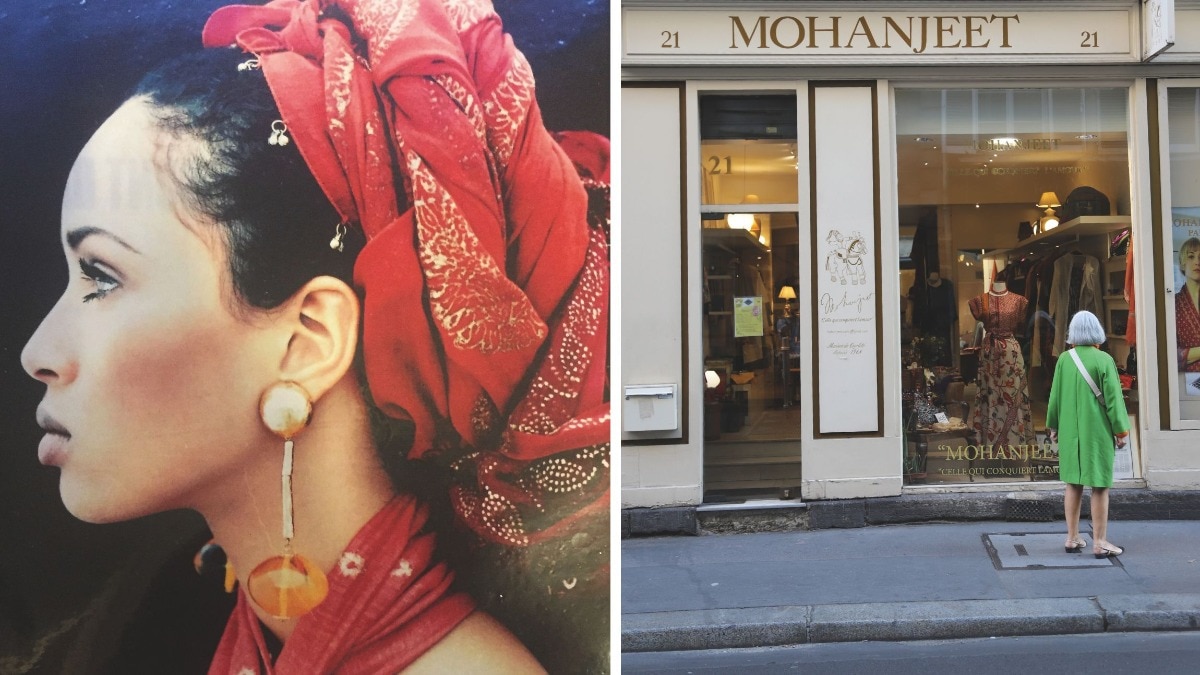

Both Yeshwant Rao Holkar II and his wife, Sanyogita Devi, were English-educated, and this changing sartorial taste was reflected in the young royals when they arrived in Paris. “When he became maharaja, Sanyogita was 15,” says Lenain. Recalling the maharani’s love for Schiaparelli, he adds, “She was like a starlet, going to parties.” Ray photographed the couple between moments of affection, generating some of the most enduring images of royal love. “It’s like the Kennedy couple,” says Lenain. “These images are highly stylised,” notes Amin Jaffer, senior curator at The Al Thani Collection. “Representing a glamorous and fashionable couple who are not only young and beautiful, but also have a deep interest in the aesthetics of the avant-garde.”

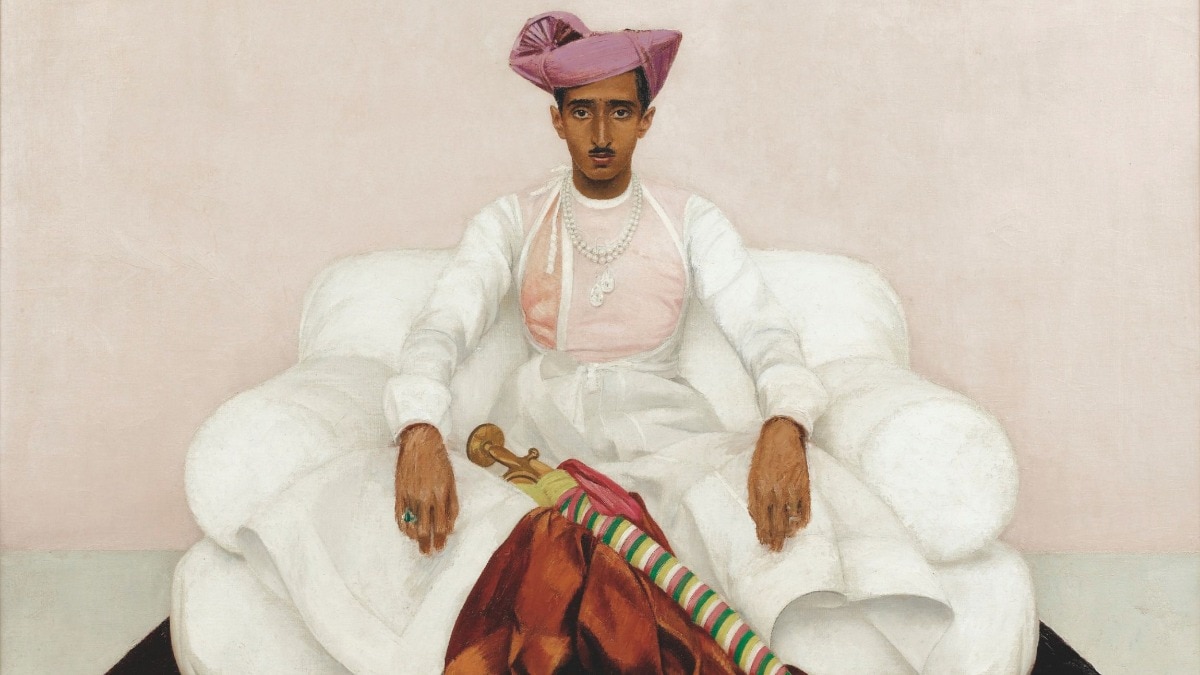

Clockwise from top: Portrait of Sanyogita Devi by Monvel; portrait of Holkar; and another portrait of the maharaja by Monvelo

Roché knew everybody in the artistic milieu in Paris, and “could introduce anybody to anybody”, Gertrude Stein, an art collector who shaped the avant-garde art movement, would write. Roché had been introducing the maharaja to artists, one of whom was the French artist Bernard Boutet de Monvel—also a fashion illustrator, who had been part of designing Jean Patou’s hotel. Intrigued by his hyperrealistic style, the couple sat for four portraits in their traditional and Western attires— which reflected the Indian and European aspects of their character, says Jaffer. In a 1931 portrait, the maharani donned a Lanvin evening gown, styling her hair into flapper finger waves, with the ‘Indore Pears’ on her neck. The twin diamonds had originally been purchased by the maharaja’s father from Chaumet, who was commissioned to transform it into a necklace—the maharaja wears this original design in a later portrait by Monvel, sitting in his traditional Maratha attire. He had taken the piece to the Parisian jewellery house Mauboussin, who followed the new art-deco style of geometric shapes and symmetry, and designed a separate piece for the maharani. “The most avant-garde thing he did is lending it to his wife to wear it,” said Lenain. “Other maharajas would not share the same jewellery with their wives.”

By then, Cartier had established itself in India and Jean Jacques Cartier was receiving many orders from the maharajas to transform their stones into jewellery. “It was all about who had the biggest necklace, biggest crown with the most diamonds,” says Lenain. “For the maharaja, it was all about modernity and simplicity—he worked with very delicate jewels.” In a photograph by Ray of the couple, he wears a single sapphire bead pendant by Chaumet. “For his personal jewels, he was going in a very different direction,” recalls Lenain. For Jaffer, the maharaja’s knowledge of the avant-garde shaped his taste and vision, defining his choices in art, design, and fashion. Roché would introduce him to the Parisian fashion designer Jacques Doucet, who was also an arts patron collecting Picasso and commissioning art-deco designers like Marcel Coard for his home—his extensive collection would influence Yves Saint Laurent in his own collecting practice, and the maharaja while commissioning designs for his Manik Bagh Palace in Indore.

Spanish Inquisition necklace owned by Tukoji Rao, passed on to Holkar II

After the maharaja passed away, Sotheby’s conducted an auction in the summer of 1980, in Monaco, of the objects and designs he had collected. “It remains the most iconic sale in design ever,” states Lenain. Yves Saint Laurent was on the front seat, bidding on items like a pair of floor lamps, created by Echart Muthesius with elements from studios producing industrial models for the modernist German art school Bauhaus. “He underbid the bed of the maharaja,” informs Lenain. The bed had been designed in aluminium and chromed metal, with glass shelves for books. The designer also bid on rugs and carpets by Ivan Da Silva Bruns, whose designs combined geometric shapes with vibrant colours. Everything was once hand-selected by the maharaja, Lenain recounts. “Everything required a stamp of his approval,” she writes. “At last, for the first time in his life, he had the last word and the power to say no. What freedom!”

This article first appeared in Harper's Bazaar India October-November 2024, print edition.

Lead image: Portrait of Yeshwant Rao Holkar II by Bernard Boutet de Monvel

Also read: The return of the cross pendant

Also read: What does luxury fashion mean to the new generation of Indian creatives?