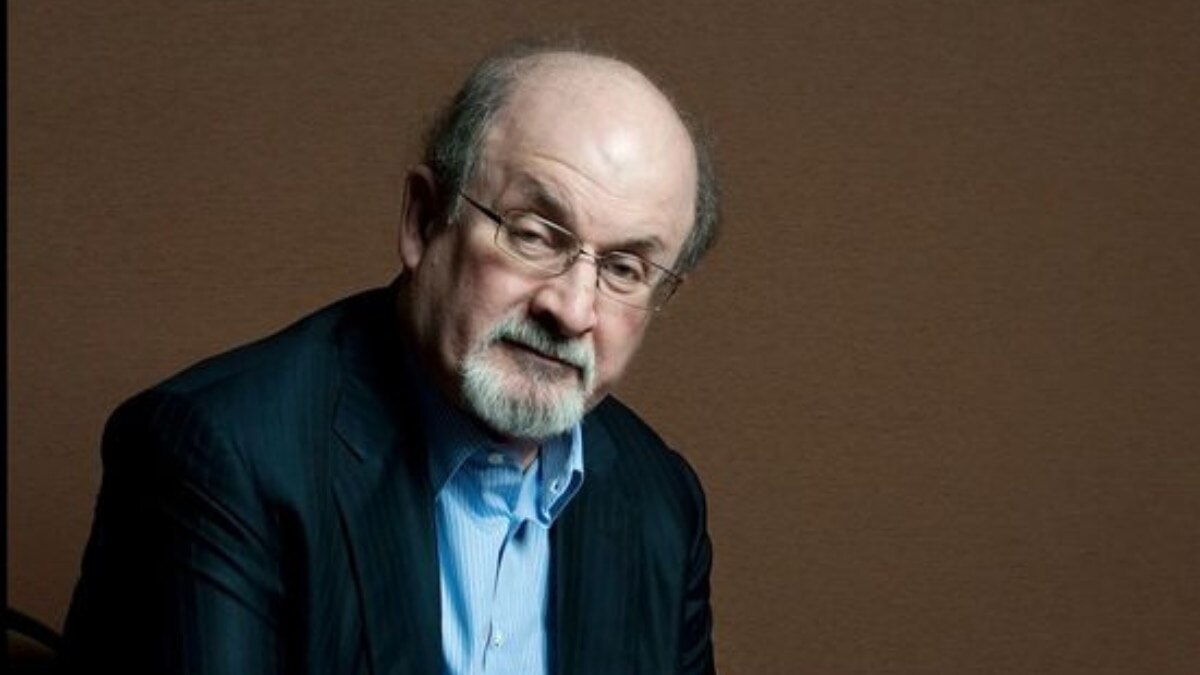

Celebrating the literary genius and indomitable spirit of Salman Rushdie

Erica Wagner on her dear friend and beloved storyteller.

Victory City, Salman Rushdie’s beautiful, powerful new novel, begins with a wounded little girl. It opens in southern India in the 14th century: in the aftermath of a battle, the widows of the defeated soldiers commit mass suicide by self-immolation. The nine-year-old Pampa Kampana’s father died long before the war, but her mother walks into the fire, and the little girl watches as her flesh is consumed. In that harrowing moment, the spirit of a great goddess enters Pampa Kampana and her destiny is sealed. She will live for centuries; she will establish a magnificent kingdom, but her triumphs will be tempered by suffering, and her wisdom is the deepest understanding of loss.

Rushdie’s 15th novel was completed before the dreadful attack that nearly took his life. In August last year, he was about to speak at the Chautauqua Institution in New York state when a man rushed onto the stage and stabbed the author at least a dozen times. Members of the audience helped pull the attacker off, and Rushdie was airlifted to the hospital. Of course, I was horrified by this appalling brutality—as was the whole world—but it was especially affecting as I have been lucky enough to call myself his friend for the past 15 years.

We’d gone out for a drink in Manhattan just a few days before. On that night, Rushdie had ordered an Old Fashioned and was in a buoyant mood. After the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988, Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s supreme leader, denounced the book and issued a fatwa against Rushdie. But the years he had spent in hiding as a result—and about which he wrote so poignantly in his memoir Joseph Anton—seemed long gone. He was living an ordinary life—if ordinary meant friendship with Bono and being awarded the Best of the Booker prize for Midnight’s Children. In the cosy armchairs of a downtown club, we chatted happily about the history of New York, the city where I was born and that he has called home for over 20 years; we talked about his Substack column, ‘Salman’s Sea of Stories’; he spoke about how much joy teaching at New York University brought him—he is the Distinguished Writer in Residence on the journalism faculty there. That’s what I recall most vividly from our last meeting: how delighted he was to be able to draw inspiration from young writers. It was two hours full of laughter—and stories.

For Rushdie is, above all else, a storyteller, and he is, by inclination and default, one of the most powerful defenders of story we have. Victory City: what a fitting title for this novel that seems, on the surface, an enchanting fairy tale, but demonstrates too the dark power of narrative, how those with authority will attempt to control the story, to spin tales that force others into subservience. Rushdie knows from experience that the flap of a butterfly’s wing can tip the balance of events. It’s apt that the opening skirmish at the start of his new book is referred to as a ‘no-name battle’ and ‘insignificant’; that the defeated kingdom was ‘tiny’, its fortress ‘fourth-rate’. Pampa Kampana—a glorious female lead—is, by contrast, empowered, as we all can be, by a mysterious mixture of accident and action.

Stories are never just stories. They are the truth of us as human beings; they are the way we shape our world. Religion is a story. The law is a story. Politics is a story. It is why stories, and storytellers, are powerful—and dangerous. The trouble comes when we try to reduce the tales we tell to binaries: good versus bad, friend versus enemy. ‘The Arabic equivalent of the formula “once upon a time” is kan ma kan, which translates: “It was so, it was not so”,’ Rushdie wrote a few years ago in an essay entitled ‘Very Well Then I Contradict Myself ’. ‘This great paradox lies at the heart of all fiction. Fiction is precisely that place where things are both so and not so, where worlds exist in which we can profoundly believe while also knowing that they do not, have not, and will never exist. And in our age of oversimplification, this beautiful complication had never been more important.’

Salman Rushdie, dear friend and beloved storyteller, is on the mend. He has lost sight in one eye and the use of one hand, as the nerves in his arm were severed. But the attacker who wished to silence him could not; indeed, he has only amplified his voice. Victory City is a victory for Rushdie—and for every reader who enters its gates.

‘Victory City’ (₹620) published on 7 February