What is the role of women in the evolution of the modern watch?

A stroll through history uncovers the crucial part they played in the design.

How rich is the history of women’s watches? At the outset, it’s worth noting two points. One, in respect to how the modern wristwatch came to be, women—not men—are at the centre of the story.

And two, though within the watch industry a lot of bragging is done about which company was the first to do this or the first to do that, there is only one company that can rightfully claim to have designed the first wristwatch as we know it today.

The story begins with Breguet. Abraham-Louis Breguet set up his watchmaking workshop in Paris in 1775, making Breguet one of the world’s oldest watch brands. Thirty-five years later, in 1810, he’d created something unprecedented for Caroline Murat, queen of Naples: a watch designed to be worn on the wrist. Today, despite the best efforts of historians and collectors, the whereabouts of this timepiece remain unknown. Further, no one can find Breguet’s preliminary sketches or a single replication of the historic piece.

So, how can we know what this watch looked like, and even whether it was a wristwatch at all? Well, based on Breguet’s workshop service records (which include an order for a timepiece “mounted upon a bracelet”), it’s believed to have been oblong in shape, with a very delicate guilloché silver dial with Breguet numerals, and to have featured several complications, including a minute repeater, a moon-phase indicator and a thermometer, making it an astonishing feat for the time. And thanks to its wristlet of hair and gold thread, this piece could be worn on the wrist.

“It’s a beautiful story that brings together the king of watchmakers and his most loyal customer, Caroline Murat, the queen of Naples,” says Emmanuel Breguet, vice president and head of patrimony, Breguet. “When Caroline ordered her watch on 8 June, 1810, she had already bought 17 watches and clocks from the master in he preceding years. Did Breguet come up with the idea of a watch designed to be worn on the wrist on his own? Or did Queen Caroline come up with the idea? I feel like saying that this incredible piece is perhaps a cocreation, the spectacular result of a dialogue between these two personalities. The Queen was certainly delighted with this unique watch, as she ordered another fifteen timepieces from Breguet!”

Thanks to the mason’s archives, Breguet adds, we know that this wristwatch, the Breguet No. 2639, was a watch with an entirely original architecture and level of refinement. It arrived at a time when the only feasible and fashionable way to tell the time on the go was by reference to a pocket watch (for men) and a sautoir watch (for women). The sautoir watch—a timepiece attached to a chain and hung around the neck—would later become a symbol of empowerment and social freedom for women during and after World War I.

In 1868, Countess Koscowicz of Hungary commissioned Swiss company Patek Philippe to design a piece of jewellery that could double as a watch, setting a trend for timepieces to be envisioned as both ornamental and functional objects inspiring great desire; Queen Victoria subsequently owned two Patek Philippe wristwatches. Naturally, these revolutionary pieces, most of which were commissioned by members of high society, came with price tags that put them out of reach of most people.

It wasn’t until the end of the 19th century that the wristwatch became a mainstream accessory for both women and men. And later the craft of watchmaking as we know it today, came into being around the time a French watchmaker and jeweller by the name of Louis Cartier created one of the earliest iterations of the men’s wristwatch for his pilot friend Alberto Santos-Dumont.

This was 1904 when a groundbreaking creation emerged: a timepiece that could be worn on the wrist while flying. Naming it the “Santos”, Cartier recognised that this watch could be of use in the bold new world of aviation, assisting a pilot on his flying journey and on the frontlines of the Great War. For women, all the while, wristwatches were a coveted accessory, a symbol of both status and opulence.

The success of the Cartier Santos helped make the wristwatch society’s most in-demand accessory. It also drove developments in women’s watches in the post-war period, which coincided with the start of the Art Deco era. Strange shapes, bold colours and the use of precious stones were all common characteristics of watches of this period, headlined by brands such as Cartier, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Piaget and Van Cleef & Arpels. This was also a time when ‘secret’ watches were devised—a charming innovation of watchmakers and jewellers, who were tasked with creating a watch that women (who weren’t thought to need to know the time at all) could check discreetly, one where a tiny dial was concealed by a bejewelled cover.

“We know that a watch is predominantly designed on a bracelet, but a watch can also be a necklace or a brooch or an object or a box,” says Nicolas Bos, CEO of Van Cleef & Arpels. “And that’s really how Maison Van Cleef & Arpels started to create watches at the beginning of the 20th century. Today, we pay homage to the Art Deco aesthetics of watch and bracelet designs that were created in the ‘30s and ‘40s through our Ludo Secret Watch collection.”

Another key consideration around women’s watches of the time was size: for one to be worn on the wrist, the dimensions of a standard timepiece had to be greatly reduced, opening up all manner of creative possibilities. No longer were watches limited to the traditional confines of round shapes; time could be expressed through a range of geometric forms—rectangles, squares, ovals, even trapezoids.

Perhaps Queen Elizabeth II’s Jaeger-LeCoultre comes to mind. It was fitted with the world’s smallest mechanical movement, Calibre 101 (this was deliberately designed as a way for Her Majesty to discreetly check the time during her Coronation, in 1953). Even as society changed and women’s roles within it evolved, ladies’ watches remained stubbornly petite for many years to come. A few more key players in the development of women’s watches cannot go unmentioned. In 1933, Blancpain appointed Betty Fiechter as its CEO, making her the first woman to run a Swiss watch manufacturing company and signalling the start of a new era and direction not only for Blancpain, the world’s oldest watchmaker, but also for women’s watches—and women in watches.

Betty, who died in 1971, paved the way for various iconic timepieces, like the first automatic wristwatch for women, the Rolls, as well as, in 1956, the Ladybird Collection, defined by stylistic details like small and dainty dials, bejewelled bezels and bracelets with ornamental features. Betty also introduced a number of significant mechanical timepieces, all presenting as unimposing, elegant and beautiful much like its wearers of the time, such as Marilyn Monroe, who owned a unique ‘30s cocktail watch crafted in platinum and paced with 71 round-cut diamonds and two marquise diamonds.

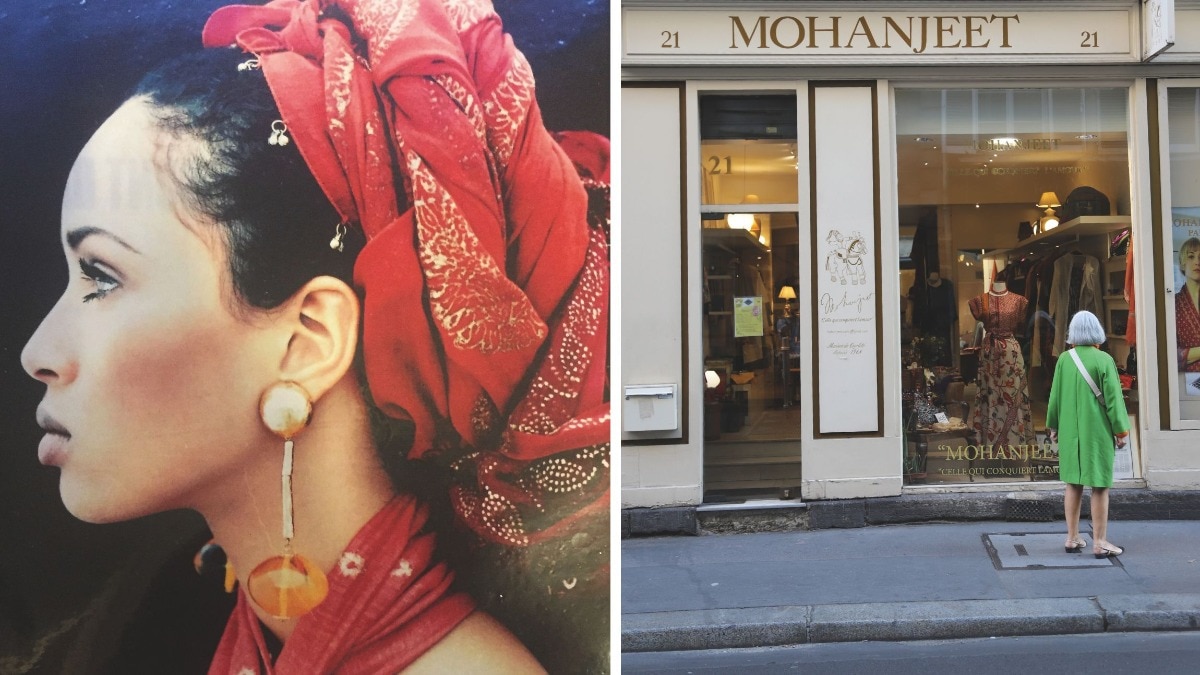

Similarly, Jeanne Toussaint, Cartier’s creative director from 1933 to 1970, was another inspirational figure who shook up the industry. Renowned for her penchant for exploring figurative and abstract creations, Jeanne spearheaded designs such as the Panthère de Cartier, one of the most recognisable and collectable pieces in Cartier’s history, as well as the Cartier Baignoire, a watch that became a cult status symbol, worn by the likes of iconic French actors Catherine Deneuve and Mélanie Laurent.

Today, there’s no denying the impact of women’s wristwatches on the wider watch industry. Even during the last decade, we’ve seen several heritage brands nod to their history, tapping into a newfound appreciation for all things vintage. And as the popularity of watches continues to grow, we’re seeing watch brands dedicate specific pieces and collections to a unisex market, as opposed to siloed categories. This, as Brynn Wallner of Dimepiece puts it, is because “women in the watch world are completely fed up with the ‘pink it and shrink it’ mentality, and we’ve gotten to a point where timepiece gender labels are nearing extinction”.

Feature Image: Van Cleef & Arpels Secret de Coccinelle watch,

Read Also: Cartier CEO Sophie Doireau talks about an initiative that promotes women entrepreneurs

Read Also: These printed scarves deserve a spot in your summer wardrobe