Designer Mohanjeet Grewal her journey from bohemian chic to fashion icon in Paris

The designer opens up about her childhood, familial relationships, her ties with post-Partition India, and why Paris is home.

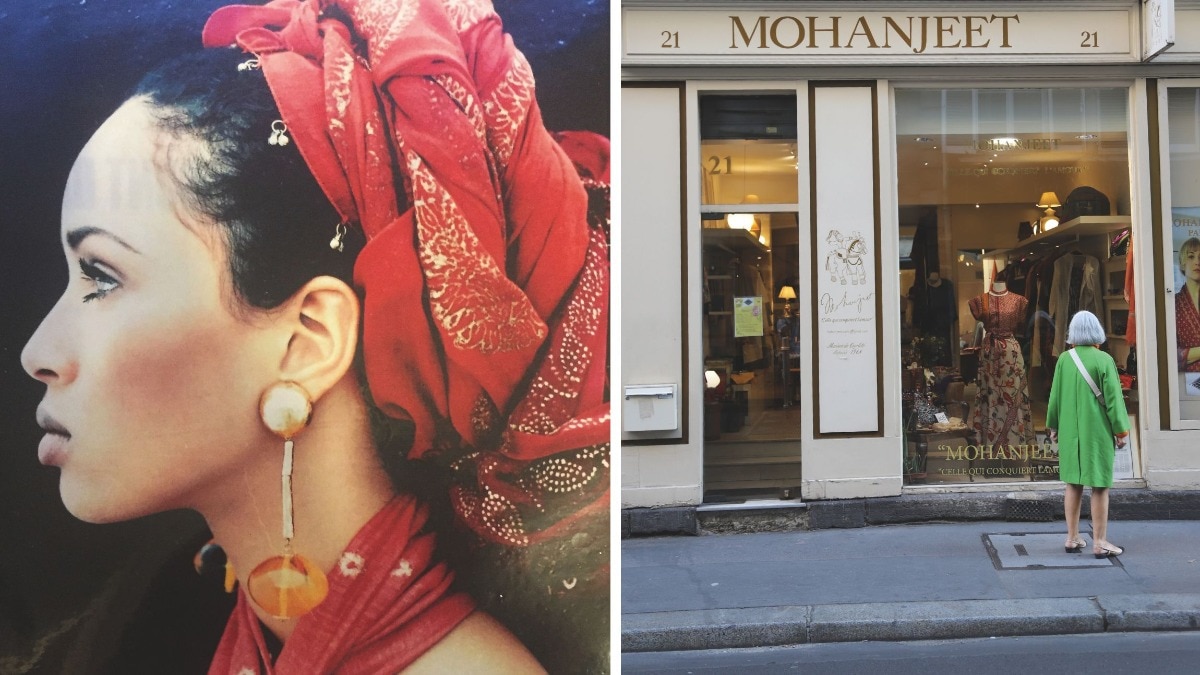

Wearing a block-printed shirt with floral printed pants and a scarf fashioned into a head wrap, German-French actor Romy Schneider sat at a table, smoking, as Helmut Newton photographed her for Marie Claire. In 1972, everything about Schneider’s bohemian chic style was straight out of the Swinging Sixties, as if she’d just returned from a Jimi Hendrix concert. Schneider was dressed by Paris-based Indian designer Mohanjeet Grewal, who had set up shop on the Left Bank, eight years ago. Now almost 60 years later, Grewal’s hair is dyed platinum blonde, and she laughs recalling her faith in herself as a young designer—the first Indian dressmaker in Paris. “I was so foolish,” she exclaims. ‘I thought I could be successful!”

Little over two decades before Grewal set up her shop in Paris, World War II had torn through the country, in the aftermath of which Dior came up with his structured female silhouette, that unravelled in the Mod era. That was exactly when Grewal entered fashion. “At that time, French women were still going to their tailors and couture houses,” she recalls. “The ready-to-wear market was just opening up.” She arrived with her khadi shirts and khari prints, which were immediately swooped up for magazine editorial spreads, and by actors like Romain Gary and Jean Seberg, who lived right opposite her store. “They were coming all the time,” she says. “They loved me.”

Barely 14 years old when Partition happened, Grewal remembers how unwilling her father was to leave Lahore until he was consoled that he could come back in two days. “But, of course, nobody could,” she sighs. The family-owned a house in Ludhiana, to which they drove surreptitiously—her father and driver trying to conceal their religious identities until they reached and were fed by the Army. “Because my father left in a baby Austin,” she laughs. “And he had bought his radio, his dog, and his white and red horns—you know, poultry! That’s all.”

Before embarking on a career as a designer, Grewal was a journalist. Her father fervently sought education for his three daughters, and she used to read The Punjab Tribune with him after his morning walk. “That’s when I started writing to the editor,” she says, and till today she needs her copy of The New York Times. She left a scholarship at UCLA after the then-defence minister of India said East Coast universities were more respectable for someone trying for the Indian Foreign Service. “I took a train to New York. I didn’t like California at all because it was very upmarket. I used to work in people’s kitchens, look after children, serve at tables in America.”

After working as a tour guide at the United Nations while studying politics, law, and literature at the Hannah Arendt Centre, she joined NYT, working with Lester Markel. She was with him when he started the daily’s Sunday issues. “I resigned because I followed someone to Vienna—which went very badly,” she shares. “So I had to leave Vienna.” Following a stint at the UNESCO office in Paris, she returned to India as a journalist. “Unfortunately, it didn’t work out at all,” she recalls. “To be a single girl and a pipe-smoking journalist in Delhi in 1962—well, people made fun. They’d come to you and say what a great journalist you are, and then they’d go to the next table and say, ‘She doesn’t know anything.’ Living in a hotel in Delhi was really adding oil to the fire.”

While in Delhi, her sister’s family said they’d like to come and see her in Paris, but they didn’t have foreign exchange. “I went to see Prime Minister Morarji Desai,” she recalls, once again showing the incredible access she had. “I had met him in New York when I was a journalist and he quite liked me.” She pled with him to export, to no avail. “I said if you don’t help me, I’ll find a way—I’ll open my shop in Paris,” she laughs. “He said, when you open it, you come to me. I said no, because then I won’t need you. He thought I was a very spoiled brat!”

Her relationship with post-Partition India was complicated, particularly when she left for California in 1952. “When I came back, I was stunned by the beauty of things,” she says. “I remember someone sitting in Connaught Place selling the most beautiful Rajasthani saris.” When she was still in New York, she was walking down Fifth Avenue one day wearing a sari, she was stopped by someone asking if she was from Iran. “I said no, I’m Indian. She said, ‘I don’t know where it is’.” Eventually, she bought her apartment in Paris and took a truckload of textiles from India to start her first store, after the minister for external exchange connected her with a business house that partnered with her to open La Malle de l’Inde’ in a courtyard.

The post-war world inspired her, especially when British fashion designer Mary Quant revolutionised the miniskirt. “Thighs completely exposed, but they didn’t care,” she says. “England has always been quite mad—they’re much freer than the French.” That was when she designed her mini sari, complete with pleats, but with the hemline above the knee—it really took off. By then, she had already gained the favours of Vogue’s editor Diana Vreeland. “She was very fond of me, and I went to her home,” she says. “The short time I did wholesale, all the big stores were waiting for me, because Vogue had told them to come and see my collection.” Ann Taylor, Bloomingdale’s, and Neiman Marcus were all awaiting the designer, who dressed Vreeland in her gold kaftan.

“I’ve dressed every icon,” says Grewal as she talks about dressing Jackie Kennedy, who she knew from her journalism days, “Elizabeth Taylor came. Bridget Bardot came all the time—her sister lived next door to me, and she was in the shop all the time. I dressed Catherine Deneuve for a very prominent film—I refused to sell curtains to her. I said this is expensive and I’m not going to change the price.” This was also a fight she’d have with Yves Saint Laurent and Givenchy, who wanted to buy curtains and fabric, respectively. “He (Saint Laurent) used to come to my building,” she tells Bazaar India. “He ordered curtains and a taburet, and figurines of khadi—it’s in his house in Morocco.”

However, after all these years, she refuses to weave any relationship with fashion. “I don’t know what fashion is,” she says. “I love Indian textiles—it’s like clay in your hands.” Inspired by the multiple prints worn by the women in Indian miniatures, she designed a mixed print dress in 1971, which still sells. “I was mad about Rajasthani textiles,” she says, mentioning how she doesn’t sketch a design until she sees the fabric. “I did a lot of khari print and bobo print in gold and silver, as it’s called in Rajasthan.” She is also deeply in love with Bengal, and grew excited when I told her it’s my hometown. “I’m crazy about Calcutta!” she gushes, talking about a collection she had made from petticoats with cutwork embroidery she’d bought from Calcutta.

Towards the end, I strangely ask her about her zodiac. “I don’t know enough about stars,” she laughs. I look up the September birthdate she mentions—she’s a Virgo, I announce. It somehow adds up, as she talks The designer’s boutique in Paris about being completely uninformed about business and being removed from the partnership with her first store, then opening seven stores across Paris with her family—all of which, but one, shut down due to familial troubles. “I lost everything,” she muses. “That’s how stupid family can be.” However, she has very devoted clients, who followed her for decades—one of her favourite clients has 300 pieces from her. “My clients are wearing things they bought 40 years ago,” she says.

She sees herself as a very loyal person, staying close to the things she loves. This summer, she’ll rearrange her store, which her father never lived to see. She left him on the Patiala station while coming to UCLA and never saw him again. “I was always outlandish in the family. These pains of childhood never leave you.” She calls Paris her home, where her fascination with Indian classical took roots, with Zubin Mehta and Ravi Shankar playing in her house. She will hold a fashion show after decades in the next few weeks. “I’ve done a lot of variations on the mini sari after a long time,” she says, but she’s already thinking of her summer collection, which will be made from her perennial infatuation—khadi.

All images: Mohanjeet Grewal

This piece originally appeared in Harper's Bazaar India, December 2024, print edition.

Also read: Seven best blazer outfits to inspire stylish creativity this winter

Also read: Chanel dreams up a celebration of the past and present in China