These homegrown labels are at the forefront of circular and ethical fashion

Working towards a better future with a conscience and aesthetics.

The sale season is upon us, and everything in my life currently reminds me of that—be it my colleagues, my Instagram feed, or YouTube ads; you never miss the big and bold “SALE” signs. And why not? After all, we all love a good deal. But amid these constant reminders, I can’t help but wonder what happens to all the clothes we buy but hardly wear and end up tossing away.

An article in The Guardian recently points out that the Atacama Desert in Chile is now dubbed as a “global sacrifice zone” for discarded fast fashion. Heaps of clothes are dumped there, totalling 60,000 tonnes, and shockingly, none of them are defective. A similar problem exists in Kenya, which is one of the main destinations for secondhand clothes exported from the US, as reported by The Washington Post.

It’s undeniable that fashion holds immense value in our lives, and that probably explains why the global fashion industry today is worth a staggering $2.5 trillion (₹2.5 lakh crore, approximately), because no one wants to go “out of fashion”.

However, this obsession comes at a high cost. The United Nations (UN) reports that the fashion industry is responsible for eight per cent to 10 per cent of global emissions, more than aviation and shipping combined. Cotton alone uses 2.5 per cent of the world’s farmland while synthetics like polyester consume 342 million barrels of oil annually, according to a report in BBC. Dyeing processes use 43 million tonnes of chemicals per year, and this industry is one of the largest water consumers globally, contributing to environmental crises like the drying of the Aral Sea in Central Asia.

As the fashion industry’s impact on pollution, water scarcity, carbon emissions, human rights, and gender inequality grows, the need for circular fashion is clear. While one could argue that sustainability has been gaining momentum since 2019 with many brands moving towards eco-friendly practices, the 2024 Circular Fashion Index report by Kearney reveals that the fashion industry, despite making progress, still struggles to fully embrace circularity.

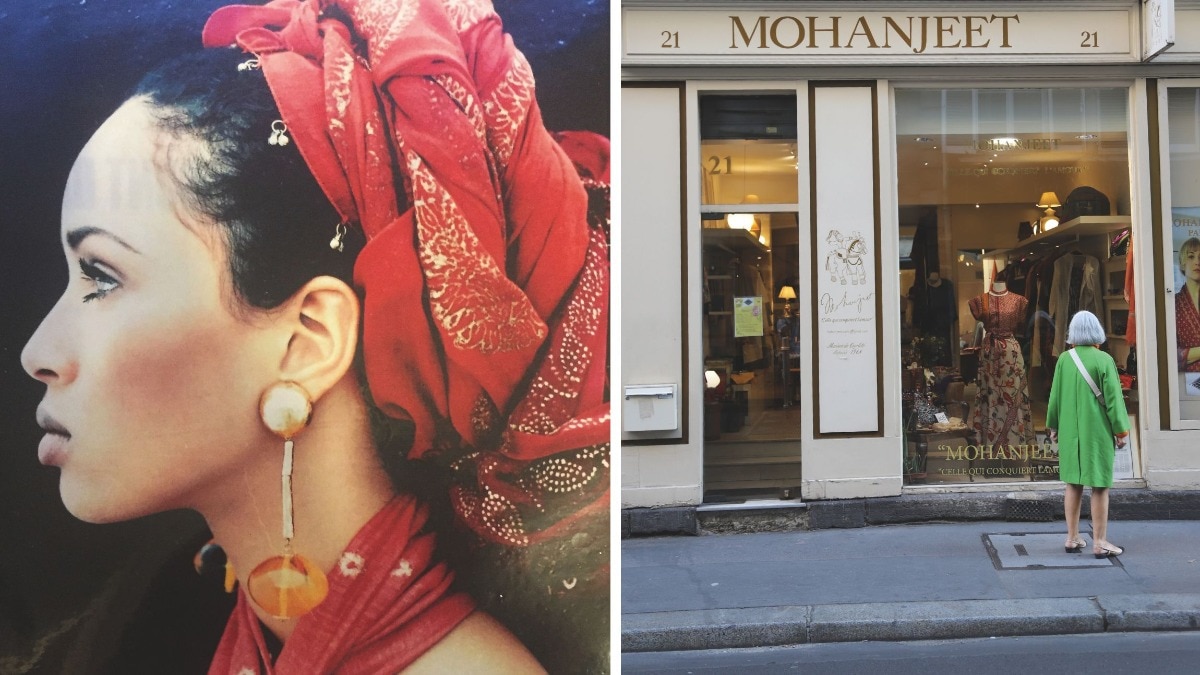

(Clockwise from left): Women forage for bast fibre and gather wild edible greens; Pochury Naga women from Meluri town in Phek district weave handspun indigenous cotton; Margaret Zinyu works with Khiamniungan artisans on different fibres

Triggered by this information, I started looking for homegrown labels, which not only prioritise circularity but also strive to address issues of human rights and gender equality. My first interaction is with 25-year-old Ashay Bhave, founder of Thaely that means ‘bags’ in Hindi. Thaely makes vegan and recycled footwear and tackles plastic waste. “Before the brand, I invented ThaelyTex—a unique leather replacement made using 100 per cent plastic bags. We wanted to keep our Indian origin in mind while conveying the message of our product,” shares Bhave as he explains the brand’s name.

Inspired by his mother’s involvement in waste management, Bhave focuses on sustainability in production. “For a product to be truly sustainable, the production has to be circular,” he says. “We prevent plastic from ending up in landfills and oceans and ensure they never become part of the waste cycle again with our returns programme.” Thaely’s returns programme incentivises customers to return old footwear of the brand for discounts on new purchases, allowing the label to refurbish or recycle the shoes.

The footwear and accessory design graduate from Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, ensures that materials like recycled plastic bags, bottles, and rubbers are both durable and comfortable. “These materials are engineered into highly durable textiles and parts, and each model rigorously tests the wearability before production. Our shoes are as durable as traditional sneakers with the added benefit of being recyclable,” he adds. Despite being in business for years, they haven’t received any pair for replacement, exclaims Bhave.

(Left to right): Thaely’s Black Raven Reflex boots and White Stork Reflex boots; Blood Red and Sky Blue Y2K Pro sneakers; Thaely Y2K Pro box made of recycled paper embedded with basil seeds and dyed with waste coffee grounds

From shoes made from plastic bags to a brand offering vintage restoration, upcycling, customisation, and heritage preservation; enters the brand Grandma Would Approve. “We make one-of-a-kind garments unique to their owners. Our circular design practices ensure nothing goes to waste. We reuse vintage garments to mend existing ones, focus on quality over quantity, and repurpose scraps into buttons and panels. Even the smallest fabric waste is collected and used as filling for winter jackets,” says Priyanka Muniyappa, who is the design head and manages production for the brand.

Over the last 13 years, the brand has built a personal rapport with around 50 vendors from whom they source materials. “This is dead stock,” says the NIFT (Bengaluru) graduate about the clothes that fill the warehouses of these vendors. “This has been sitting here for 30-50 years. During sourcing, we spend a week per warehouse, meticulously segregating and selecting garments. After washing, they’re sent to our studio and organised in our fabric library,” Muniyappa says sharing the details of the process. The upcycling process involves examining garments for defects, removing stitches, and preparing the fabric. “We replace damaged parts, remove stains, and restore the garment from a stripped-down version.”

In the reconstruction process, the label creates unique wearable art pieces. “We combine 10 to15 garments, sketch designs, and our pattern master and I plan the pieces, which can take about 12 days and sometimes involve 100 panels. These pieces are for fashion shows and international showcases,” says Muniyappa. Despite challenges, Grandma Would Approve is committed to zero waste and circular, artistic fashion. “I wanted to change this cycle and introduce something made with love, fair pay for artisans, and no environmental depletion. That’s my relationship with my brand and team—it’s very personal and intentional.”

My next interaction is with Margaret Zinyu, a Kohima native and founder of Woven Threads—a design initiative that crafts high-end loin loom textiles using sustainable materials and a zero-waste manufacturing process based on indigenous knowledge systems. An alumna of the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, Zinyu’s fascination with nature and traditional crafts laid the foundation for her future in design. “The lush landscapes and traditional crafts of Nagaland instilled in me a deep appreciation for texture, colour, and form,” she says. “Textile design is not just about creating beautiful fabrics; it’s about telling stories, preserving heritage, and fostering sustainable practices.”

Reconstructed couture range from Grandma Would Approve that was showcased at circular design challenge at Lakmé Fashion Week

Woven Threads exemplifies the power of aligning professional pursuits with a deeper purpose. “By tapping into the rich cultural heritage and traditional craftsmanship of the community, we have developed collections that resonate with a mindful consumer base and empower the custodians of these practices,” informs Zinyu. The brand has empowered women weavers in Nagaland to contribute to their household’s economic stability.

“The loin loom or body-tension loom is practised in Northeast India and around the world. It features a strap fixed to one end, worn around the weaver’s waist, while the other end is anchored, making it portable and unique.” Zinyu highlights two non-timber forest products: wild orange rhea plant and Himalayan stinging nettle, valued for their colour, strength, and cultural significance. Known locally as Elloinui (bast fibre), these plants are integral to the Khiamniungan community’s rich weaving traditions.

Zinyu’s design initiative was recently featured at the 2023 Serendipity Arts Festival, highlighting Nagaland’s traditions and showcasing cultural richness and environmental sustainability. For Zinyu, more than aesthetics, it’s about a holistic approach to design that considers environmental, social, and economic impacts. “Through innovative, eco-conscious practices and empowering local communities, we can shape a more sustainable future, one design at a time,” she says. All Woven Threads products are handwoven and hand-stitched, using fabric directly off the loom with minimal or zero waste.”

So, the next time, you find yourself tempted by irresistible sales, consider the broader consequences of your fashion choices. The clothes we buy have a profound effect and by choosing brands committed to circular, sustainable, and ethical practices, we can make a meaningful difference in fostering a healthier planet for future generations.

All images: Courtesy The Brands

This article originally appeared in Harper's Bazaar India, June-July 2024 print issue.

Also Read: Perfect the quiet luxury look with these homegrown sustainable brands

Also Read: How this content creator has made a case of India's textile heritage, one state at a time