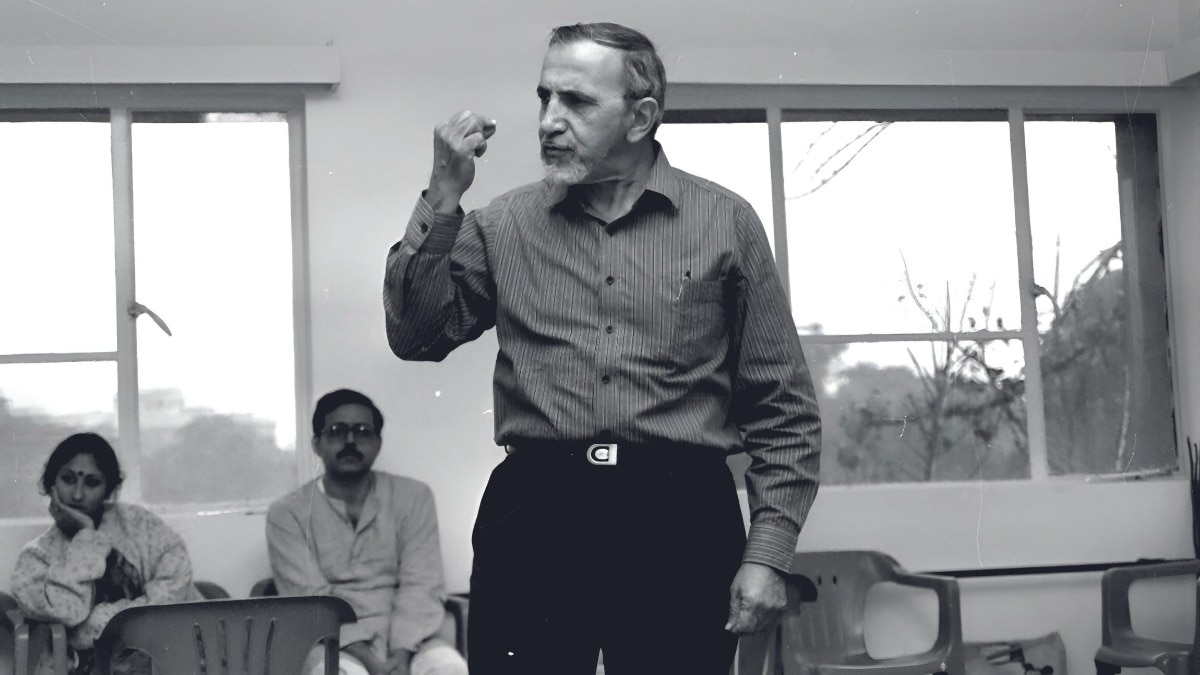

Amal Allana talks about her biography of her father, Ebrahim Alkazi

The portrait of the theatre icon chronicles his life and the challenges he faced as the director of the National School of Drama.

In the annals of Indian theatre, few names resonate as powerfully as Ebrahim Alkazi. Often hailed as the “father of modern Indian theatre”, Alkazi’s contributions are immeasurable. With her biography, titled Ebrahim Alkazi: Holding Time Captive, his daughter and author Amal Allana celebrates a life dedicated to the pursuit of artistic excellence and the relentless quest for cultural enrichment.

Born in Pune in 1925 to a Bedouin trader father and a Kuwaiti mother, Alkazi’s journey in theatre began with the English language theatre group led by Bobby Padamsee. Alkazi’s story is one of passion, perseverance, and profound influence.

Describing her father as “focused”, Allana shares the story behind the title of her book. “I had been considering several alternatives as the title, but then, serendipitously, on the day my father passed away I was looking through his papers,” recalls Allana. A small piece of paper fluttered out of his diary, and she found a couple of lines penned by her father with a shaky hand that talked about how it would be to “hold time captive”. This was when Allana decided the book title. Besides the literal meaning, she adds, “my father intended this phrase to be open to multiple interpretations, which made it intriguing.”

Allana, deeply immersed in theatre like her father, remembers how their house served as her father’s studio and workplace ever since she was born. “Furniture would be pushed aside, and rehearsals took place right there,” she reminisces. Her father involved her in all his activities. “I was cast in plays, I made posters, ushered people to their seats, and helped with costumes.”

In 1947, Alkazi went to England to study at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Despite receiving accolades from the English Drama League and the British Broadcasting Corporation, and being offered career opportunities, he decided to return to India. In 1954, he established his own theatre unit, bringing a professional and technically advanced approach to theatre, encompassing stage management, character development, lighting, and props. A few years later, he relocated to Delhi and assumed the directorship of the National School of Drama—a role he held until 1977.

This role, however, was not without challenges. Allana explains that from the late 18th century, playwriting and theatre companies evolved into commercial enterprises in cities like Bombay and Calcutta. Indians enthusiastically embraced modern theatre because it was based on the new concepts of Western proscenium theatre, both in staging and writing. They were partially indigenising theatre to create “novel kinds of operatic forms like sangeet nataks, which developed in languages like Urdu, Bengali, and Marathi,” she says.

However, after Independence, the usage of Urdu declined as Hindi was proposed as the national language. Since none of the plays were available in Hindi, Allana states, “Alkazi rapidly enriched Hindi theatre by getting plays translated into the language. Newly written plays in Marathi, Bengali, and Kannada were also translated into Hindi.” Alkazi built open-air and studio theatres, and ensured regular performances every weekend. This effort cultivated a theatre-going habit among the Delhi audience, putting Hindi theatre on the map.

One might assume that Alkazi’s time in England influenced his plays upon his return to India, but Allana disagrees. “Even though Alkazi’s plays in the early years included a large number of Western works, they were carefully selected for themes that could relate to the circumstances prevalent in India at that time.” She further clarifies, “Whenever Alkazi analysed a play for his actors, he always made them understand the deep connections these plays had to their own country and society.”

Despite the significant contributions of Alkazi, information about his life and achievements remains sparse. “No theatre critic or historian settled down to understand where Alkazi’s thinking and approach stemmed from. He was creating ‘performances’ and teaching theatre as a ‘performance’ rather than as ‘dramatic literature’, explains Allana. “Theatre direction in the way Alkazi practised was a relatively new concept in 1950s. He was part of the first generation of Indian theatre directors.” No wonder, his legacy continues to inspire future generations.

Image Courtesy: Shobha Deepak Singh

This story originally appeared in the June-July 2024 print edition of Harper's Bazaar India.